Serial

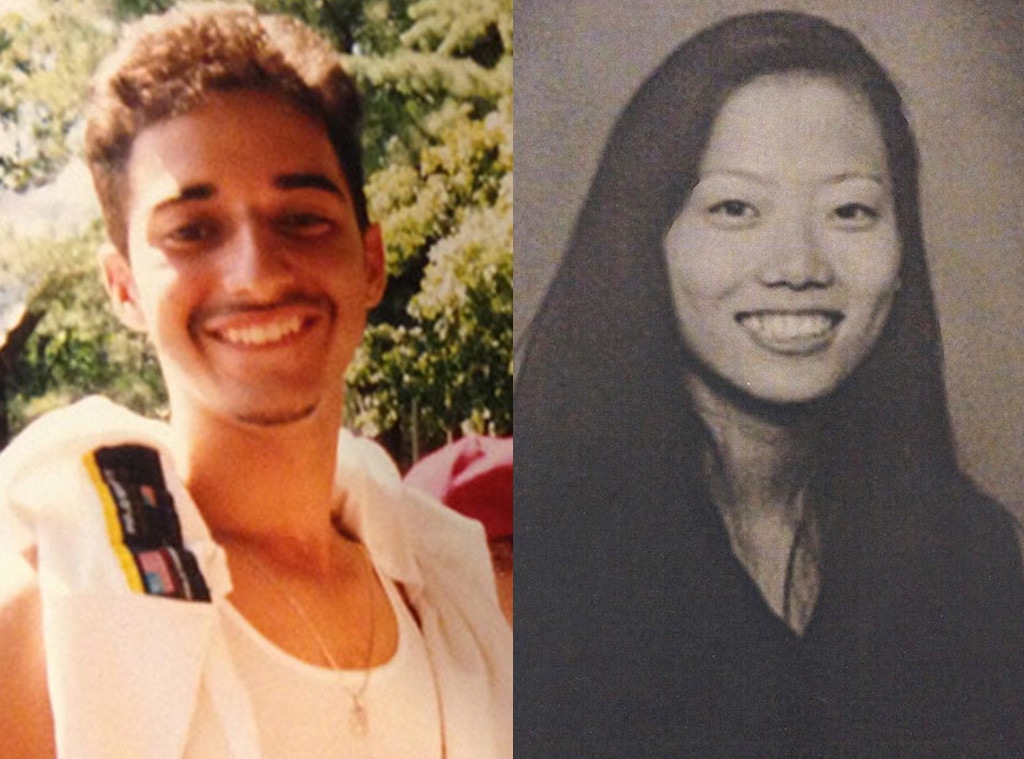

SerialTwo days before part one of The Case Against Adnan Syed premiered on HBO, the Maryland Court of Appeals reinstated the murder conviction vacated by a Circuit Court judge in 2016.

The 4-3 decision handed down by the state's highest court smashed the hopes Syed and his avid group of supporters had for a new trial in the 1999 slaying of 18-year-old Hae Min Lee.

So what in the heck were we supposed to be watching, more than four years after the smash-hit podcast Serial turned Syed's case on its ear, other than another epic study in frustration?

"I think we go much deeper now because time has helped us, and Serial has helped to unearth a lot of new information, so hopefully we're much closer to the truth now," director Amy Berg told E! News ahead a month before the docu-series' premiere.

And therein lies the rub.

"I think Adnan probably did it, but this case reeks of reasonable doubt," ABC News legal analyst Dan Abrams told Nancy Grace in 2018 in one of numerous snippets of the Serial-inspired coverage of the by then 19-year-old murder case woven throughout the four-part HBO show.

As Serial host Sarah Koenig noted when accepting her Peabody Award—the first ever for a podcast—in 2015, her accidental cultural sensation was "a 10-hour audio documentary about an old murder that [she] did not solve."

She did not, as she has said, set out with an agenda, to prove Syed's innocence or guilt. She merely sought to lay out the circumstances of the case, the investigation and the two trials—a mistrial was declared during the first—that ended in a 19-year-old Syed being sentenced to life in prison for murder, plus 35 years for kidnapping.

Serial set off a still-raging did-he-do-it debate and triggered an epic flood of true-crime podcasts, the popularity of which have not dimmed. Koenig—who had written about the 2000 trial for the Baltimore Sun—took no outward position on whether or not Syed killed Lee, who by the time she disappeared on Jan. 13, 1999, was his ex-girlfriend. But what she laid out in Serial did poke serious holes in the process that led to his conviction, enough to lead all the way to a judge agreeing in 2016 that Syed was not adequately defended at trial.

The key reason Baltimore Circuit Court Judge Martin Welch cited: cell tower data supposedly pinning Syed's location at key times on the day Lee disappeared gleaned from cell phone records was unreliable and his attorney, Cristina Gutierrez, didn't use information she had (from a faxed cover sheet sent with the records) to challenge the prosecution's expert witness. Welch did not think that their other main point, that Gutierrez failed to call Asia McClain as an alleged alibi witness, to the stand, was as potentially consequential to the outcome.

Rabia Chaudry, an attorney and friend of the Syed family who was in law school when she reached out to Koenig about what she and Adnan's family maintain was a gross miscarriage of justice, hosts the podcast Undisclosed and features prominently in The Case Against Adnan Syed—which further dissects the process that led to where we are today.

Or, not today-today, because Syed is not where any of his advocates in the HBO series hoped he would be by now.

The middle son of Pakistani immigrants with strong ties to the Muslim community in Baltimore, Syed, who's now approaching his 38th birthday, has been described as a typical teenager: a good student who played football and fussed over his hair, smoked pot, had a diverse group of friends, was crowned prom prince and kept his dating life secret from his strict parents.

His close-knit community would be used against him at his bail hearing, when the prosecutor argued that he had the resources of his fellow Muslims at his disposal and an uncle in Pakistan who could help him disappear should he flee the country. He was remanded without bail and hasn't been out of custody since.

Syed's sunny anecdotes—as in Serial heard but not seen—about his friends, high school and dating Lee are engrossing and remain all the more jarring when you remember that he's relaying them from prison, where he's now been for 20 years.

New to the telling of this story is the renewed focus on Lee, whose words—taken straight from her journal (with a cover depicting Monet's "Waterlilies" that she purchased on a trip to a museum with her French class)—open the series.

"This book is open to those whose heart is innocent. If you feel any guilt reading this, you should stop. This book is full of my expression. This may make you: angry, happy, mad, or/and cry, so do enter at your own risk. Dedicated: to those who I love and love me back—do love and remember me forever, since I'll always love you all."

Of course it's meant to be haunting.

And though Chaudry has been fighting not just to correct a legal mistake, but to free a man she believes is innocent, she reiterates that the search for the truth means justice for Hae Min Lee as well.

"My prayers are always not just that Adnan's exonerated, that God brings truth to light, because that is justice for Hae," she says in the series.

You quickly realize from the beginning of The Case Against Adnan Syed how vital Hae's voice—which couldn't help but get lost in the nuts and bolts of the murder investigation—is to the proceedings, and the film enhances the archival photographs, news clips and trial footage it has in a most touching way, with hand-drawn animation inspired by the romance, optimism and intense swings of teenage emotion found in Lee's diary. Or her "memoire," as she titled it.

Lee was also a member of a close-knit, strict immigrant family, and Syed shares in the docu-series that she had told him during their relationship that she was sexually abused as a child in Korea and the perpetrator never faced consequences. A friend of Lee's confirms that she also told her about the abuse, but wouldn't have wanted that sort of private information to come out at trial.

She in turn kept her love life as much of a secret as possible, as did Syed, whose family didn't believe that Adnan was dating because he was getting such good grades. But for all of Hae's interest in Adnan at first, as we knew from Serial and which is spelled out in no uncertain terms in her journal, Lee was "in love" with 22-year-old Don Clinedinst, a co-worker from her part-time job at Lenscrafters, by the time she died.

(In a cryptic moment in the show, Don is heard telling the filmmakers when they went to interview him in North Carolina in 2017 that he had been on disability since he was 23, he didn't expect to live to see 50 and his main concern was providing for his wife and kids.)

The Case Against Adnan Syed took years, but when it was initially finished, his petition for a new trial had been granted, pending the result of the state's second appeal, giving the series' build-up to a conclusion that wasn't guaranteed, but of which there was much promise, a certain structure.

Since Serial, which prompted new people to come forward with evidence in Syed's case, the culture surrounding how the story of major crimes are told has changed—or, if the wheel hasn't been reinvented, the elaborate wheel has become more mainstream. The Oscar- and Emmy-winning O.J.: Made in America set the gold standard for contextual re-examination of a crime, in how it dove deep to tell the story of Simpson's celebrity, the history of Los Angeles law enforcement and the fractured relationship between police and people of color in the city in the wake of the not-guilty verdicts against cops caught on video beating Rodney King in 1992.

Meanwhile, 2015's Making a Murderer made a very convincing case—strategically and subjectively, according to critics of the filmmakers' approach—that authorities had it out for Steven Avery when he and his cousin Brendan Dassey were arrested for and subsequently convicted of the 2005 murder of Teresa Halbach. Dassey's conviction was overturned in 2016, with a judge agreeing that his confession was coerced by investigators. The decision was upheld by a three-judge panel from the U.S Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, but then overturned when reviewed by the full 11-judge panel. Last June, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case and Dassey remains in prison.

The Case Against Adnan Syed delves somewhat into Baltimore's ongoing crime problem when Lee was killed, as well as the prejudices facing both the city's Muslim community (if you thought that started on 9/11, you're sorely mistaken, Chaudry notes) and its largely working-class population of Korean immigrants.

Hae's was the 20th body found in Leakin Park—dubbed the "city's graveyard"—in five years. While other major cities around the country were seeing decreases in violent crime, the murder rate was on the rise in Baltimore.

And plenty of people didn't trust the police.

As the series traces the shifting recall of events supplied by the prosecution's star witness, Jay Wilds, Chaudry states her belief that the police helped Jay "craft a story"—after zeroing in on him in the first place thanks to "cell phone and cell phone records" that would prove so problematic. The fuzziness of what Jay told police was amplified by the testimony of his friend Jennifer Pusateri, seen in archival footage and in new interviews for the series, whose house Jay spent time at the afternoon he claimed he helped Adnan bury Hae Min Lee after Adnan strangled her inside her Honda in a Best Buy parking lot.

Jenn testified that Jay told her that Adnan had told him that he had killed Hae in the Best Buy parking lot; she says in the show she didn't find out until two weeks before Syed's murder trial started that Jay had also helped bury Hae.

He first told police he did not help bury Hae, but admitted to supplying Adnan with a shovel. Earlier in the day Adnan, Jay said, Adnan had said he was upset at Hae for dumping him, then he loaned Jay his car to go buy Jay's girlfriend Stephanie a present, saying he could pick him up at track practice at the high school later. Instead, Adnan (a friend, but not a close friend, according to multiple accounts) called him at Jenn's to pick him up at the Best Buy, where he showed him Hae's body in the trunk of her car. Adnan and Jay then went back to his friend Cathy's house to smoke pot, but Adnan got a phone call and left. Wilds later testified at trial that he did help Adnan dig the grave.

If this sounds convoluted, it is, because it took two police interviews with Jay, two weeks apart, to get the story that was later used at trial at least somewhat straight.

But in the meantime, not long after police concluded their first interview with Jay in the wee hours of Feb. 28, 1999, Hae's car was found parked on a remote side street behind a string of row homes.

A few hours later, Syed was arrested.

"I think that Jay knew where the car was the way he knew everything—someone told him," Chaudry says.

The discovery of Hae's car, purportedly six weeks after Adnan and Jay abandoned it in that lot, gets a deep dive in the show from Luke Brindle-Khym and Tyler Maroney, private investigators commissioned to review the evidence against Syed. First they spoke to a longtime resident of the neighborhood who insisted that no unfamiliar car would've been parked there all that time without someone calling 311 or police.

Brindle-Khym and Maroney also enlisted a turf physiologist, Dr. Erik Ervin from the University of Delaware, to help determine whether the grass under Hae's car had the characteristics of grass that had a car parked over it for six whole weeks.

The results of Ervin's simulation experiment were reserved for Sunday's series finale: his grass samples (grown in patches to mimic the weather conditions over that time frame) did not provide a definitive conclusion as far as how long that grass was exposed to the elements or not, but he was "very surprised" to see so much fresh-looking "detritus" in the tires looking at photos taken of the car once it had supposedly been sitting there for six weeks.

The private investigators also puzzle over the more than 20 times Jay was arrested or otherwise had a run-in with police since 1998, for infractions ranging from assaulting a police officer to possessing a loaded shotgun to domestic violence, and was never prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

An ex-girlfriend of Jay's, Nikisha Horton, who said he once beat her up in the car while her son was sitting in the back seat and shows photos of her bruised face, also sets off to look into his past in 2016 in the wake of the Serial publicity. She gets Jay, purportedly living in California at the time, on the phone for the first time in ages and relays, after a brief chat, that he basically told her he gave the cops the story they wanted to get himself off the hook for being caught with a ton of weed.

"I know it's probably eatin' him up," Horton says.

In Serial it was revealed that Woodlawn High classmate Asia McClain said she was never contacted by Gutierrez, who died in 2004, in response to her letter saying she remembered seeing Adnan in the library the afternoon Hae went missing, right during the time prosecutors said she was killed. She recalls in Part 3, "Justice Is Arbitrary," that prosecutor Kevin Urick dissuaded her from getting further involved, saying they had DNA and a witness who said he helped Adnan bury Hae's body.

McClain says she didn't find out until she listened to Serial that they had never tested any DNA they collected from the crime scene or where Hae's body was found.

When McClain saw Urick testify at a 2012 hearing on first Syed's petition for post-conviction release that she told him she had written her letter and signed an affidavit under pressure from Syed's family, she felt terrible.

"It was like being punched in the gut," Chaudry says. "It was a total lie."

After Serial aired, McClain reached out again to get a new affidavit on the record in which she swore she was not influenced by the family in any way. "[Urick] convinced me to stay out of it," she reflects. "It pisses me off. It makes me hate myself for allowing him to manipulate me in that way."

Part 3 also delves into the faulty cell tower data, which Chaudry helped bring to light with the help of attorney Susan Simpson, who while Serial was underway wrote a treatise about Jay's testimony on Reddit. Chaudry took notice, reached out and sent her all of her files on Adnan's case.

"They get their [cell site] maps and they realize they've got some very big problems, because Jay's story is not matching cell phone records," Simpson says.

So detectives called Jay in for a second interview—and eventually his story lined up.

"You don't turn on the tape recorder until you've got the statement you want," Simpson says.

"I mean," she adds, "Jay was a teenager. A black guy in Baltimore being interviewed by homicide detectives, who are telling him they want him for a murder. And the cops are very good at convincing people your best bet is to talk yourself out of [your predicament], when really all you're doing is talking your way way-way into it."

Simpson says Det. William Ritz, who helped question Jay, was involved in three other cases that resulted in exoneration or a conviction being overturned, including one in which Ezra Mable, who'd been in prison for 10 years for murder, was exonerated due to his own legal work. In a civil lawsuit, he alleged the Baltimore police's "web of intentional bungling and concealment of exculpatory evidence throughout all phases of their investigation" led to his wrongful conviction. Ritz was named as one of the defendants in the man's 2013 complaint against numerous Baltimore officials.

Syed's attorney, C. Justin Brown, tweeted about another lawsuit filed against the Baltimore City police department in February, also naming Ritz, who was lead investigator on the case; Malcolm Bryant was convicted of murder in 1998 and had his conviction vacated in 2016 with help from the Maryland Innocence Project.

Simpson continues to poke through holes in the cell phone records, including a convenient typo that placed Jay further west, closer to the Best Buy where he supposedly got the call from Adnan to go get him, than at Jenn's house, where the correct cell code would have placed him.

"At that time I was halfway between my house and Jenn's house," Jay told police in that second interview. "And he told me to meet him at Best Buy."

Jenn testified at trial that Jay first left between 3:40 and 3:45 p.m. Jay also told police he left at about 3:40.

"He both left to go to Best Buy at 2:36 when the 'come and get me' call—but he also didn't leave Jenn's house till 3:40," Chaudry says. Adds Simpson, "I mean, the story's nonsense. It came from nonsense, and it was multiplied by the cell phone records. They kept introducing errors they'd have to correct again."

Moreover, as previously touched on in Serial, they explain in detail (it does help to see snippets of affidavits in black and white) the issue with the cell tower data. Simpson shares how the prosecution's expert, engineer Abraham Waranowitz, did not know when he testified about pinpointing locations using cell towers that AT&T had issued a disclaimer that only outgoing calls were reliable for determining location status, while incoming calls were not.

Detectives had built their case relying almost exclusively on incoming calls.

"If I had been made aware of this disclaimer, it would have affected my testimony," Waranowitz stated in a signed affidavit.

Kevin Urick told The Intercept in 2015 that he wasn't bothered by the moving pieces of Jay's story, nor did it matter to their case that his recall of where he was at a given time on Jan. 13, 1999, didn't precisely match up with cell tower triangulation.

"I do not remember that at any time we had any dissatisfaction with the evidence of the cellphone records and how it meshed with Jay's story," Urick, who left the state's attorneys office for private practice, said. "No one is capable of perfectly remembering exactly what time they were at a particular place, or even where they were every time a call is made or received. Some discrepancies would be expected."

Urick said that he did not respond to any interview request from the producers of Serial (he said there was one, they said there were many) because he was an advocate for whom he saw at the real victim in the case. "This was a young girl killed at about age 18," he said. "When you deal with victims as a prosecutor, sometimes you have to put [their families through a lot]. But this was 14 years after the fact. I did not want to be responsible for causing any further anguish for the family."

He reiterated that Asia McClain told him that she had been "under a lot of pressure from Adnan's family" when she wrote those letters.

Jay Wilds, who in 2000 received a suspended five-year prison sentence and two years' probation after pleading guilty to accessory after the fact, refused to be formally interviewed for The Case Against Adnan Syed but the filmmakers finally caught up with him in January, and he spoke about the case.

Originally he told police that, on the day Hae Min Lee disappeared, Adnan loaned him his car so he could use it to go buy his girlfriend Stephanie (the only person who was at his sentencing hearing a year later) a present while Adnan was at track practice at the high school. He told the filmmakers he drove to the school to return the car, but Adnan wasn't there.

He originally said in 1999 that Adnan first showed him Hae's body in the parking lot of the Best Buy. Wilds told The Intercept in 2014, however, that Adnan showed him the body in the driveway at his grandmother's house, which he didn't tell police because he didn't want to get her in trouble. Along those lines he reiterated to the filmmakers that Adnan showed him the body "at his house."

Wilds, who refused to talk to Sarah Koenig, told The Intercept that he thought he would end up with a small mention in Serial. "I thought since I didn't cooperate with her she would just make a little blurb about me in the story and then she would move on to whatever this 'new evidence' was or whatever Adnan had to tell her," he said. "I didn't think I would be demonized."

Asked by police why he thought Adnan would call him, Jay simply replied, "I'm the criminal element of Woodlawn."

Similar to what he told The Intercept, he told the filmmakers that Adnan asked him to procure 10 pounds of marijuana and, when he did, threatened to report Jay to police if he didn't help him bury Hae.

Jay also said in January that the idea of seeing the body first outside Best Buy "came from police."

Meanwhile, Brindle-Khym and Maroney pressed on, with an eye on gathering evidence to work for the defense at trial should they get there. They spoke to Fulton County Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Jan Gorniak, who, based on the lividity found in Hae's body, disputed the timeline put forth by the prosecution, which maintained that she was killed at 2:30 p.m. and buried around 7:30 p.m. Gorniak was of the opinion that lividity didn't start to set in till, at the earliest, 10:30 p.m., meaning her body was in a different position for far longer in contrast to how she was positioned in the hole dug in the park.

Twelve DNA samples taken from Hae's body and car, including from fingernail clippings, a condom wrapper and a liquor bottle—none of which the state ever submitted for testing before Brown initiated the testing last summer—did not match Adnan. A fingerprint lifted from the car's rearview mirror were not a match to anybody in the system, nor was the DNA.

"NOTHING was matched to Syed," Justin Brown tweeted last Thursday. "There is no forensic evidence linking him to this crime."

'These results in no way exonerate him," countered Raquel Coombs, spokeswoman for the Maryland Attorney General's Office, in a statement to the Baltimore Sun.

"While these DNA results do not reveal the true killer, they do go a long way in showing that the wrong person is in prison," Brown wrote in an email to the paper.

Brindle-Khym and Maroney reiterate how the police never really looked hard at Hae's new boyfriend, Don, whom she was going to meet the day she disappeared. Holes could be poked in his alibi that he was on the job at Lenscrafters that afternoon, the group mused after getting in touch with the lab manager in charge at the time. Don's mom was the branch manager at the location he said he was working at—on a day when he wasn't on the schedule to be working—when his time card indicated he punched in and out.

The private investigators also mention that there could be more to know about Alonzo Sellers, the guy who reported finding Hae's body when he walked into the park on Feb. 9, 1999, to urinate. He had previously been arrested for indecent exposure and was questioned before the police turned their attention to Adnan following an anonymous tip called in on Feb. 12, 1999, advising police to check out Hae's boyfriend.

But the Maryland Court of Appeals blocked out any potential light at the end of the tunnel. Three of four judges in the majority agreed that Adnan's counsel was lacking, but not enough to outweigh the state's evidence against him. The four didn't think that calling Asia McClain to the stand would have necessarily changed anything--and one judge wrote in her concurring opinion that she didn't find Asia credible.

Meanwhile, both appellate courts, including the one the upheld Judge Welch's 2016 decision, discounted the mishandled cell tower evidence that was key to Welch's conclusion, agreeing that Syed waived his right to the claim because it was not included in his original petition in 2012 claiming he was inadequately defended. The Court of Special Appeals had turned its attention to the what-ifs attached to McClain's never-heard testimony.

The series finale included a postscript revealing the March 8 decision, as well as Brown's statement that they were "devastated" but would not give up fighting.

"There was a credible alibi witness who was with Adnan at the precise time of the murder, and now the Court of Appeals has said that witness would not have affected the outcome of the proceeding," Brown told the Baltimore Sun. "We think just the opposite is true. From the perspective of the defendant, there is no stronger evidence than an alibi witness."

They would explore "at least three avenues of relief" in the near future, the attorney said.

Legal experts say they can file for reconsideration with the Court of Appeals or try to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, neither of which would be likely to review the decision.

Adnan's family, who haven't given up hope, have their own battles to fight in the meantime. His mother, Shahmim Rahman, was diagnosed with leukemia in 2017 and his father, Syed Rahman, has been mired in depression since his son's conviction and doesn't leave their house much. Shahmim didn't tell Adnan that she was sick until late last year, not wanting to worry him.

"It's important for the viewers to see these are real people affected by an injustice and everybody who had anything to do with this case is still carrying it around 20 years later," Berg said.

Adnan eerily compared the judge ruling in his favor in 2016 to finding out he had just been "approved for chemotherapy," knowing he still had a long road ahead of him should he be re-tried for Hae's murder.

"Chemotherapy, it ravages the body," he says. "It doesn't mean it's going to cure you. Iv'e known people who've had terminal illnesses, like since I've bene in prison, that's t'he only thing I can ever equate it to. To talk to someone when they first have a terminal illness it's like, man' I'm going to beat it.' You know, 'I'm going to beat it.' And then eventually it comes to a point wher eit' slike, 'man, you know what, I'm not going to beat it.' It's going to beat me.'

Talking to E! News, Chaudry said that, throughout this whole process, what surprised her most was "how many things could've so easily been understood and documented and discovered, if investigators—or even defense counsel at the time in 1999—had done their job properly. This didn't have to be a mystery. You know, Hae Min Lee and Adnan could've both gotten justice 20 years ago."

Lee's family, meanwhile, has supported every effort the city of Baltimore and state of Maryland have made to keep Syed behind bars, believing that the person who murdered Hae has already been brought to justice.

In November, on his way to present Adnan Syed with a deal proposed by State Attorney General Brian Frosh—plead guilty and spend four more years in prison with the promise of getting out—a dejected Justin Brown said, "They're trying to figure out what our breaking point is… They've done a pretty good job of getting us to a breaking point."

To answer the question of who would ever plead guilty to something he or she didn't do, Brown said it happened every day.

"Our criminal justice system is not always fair, it's not always right," he said. "This is reality."