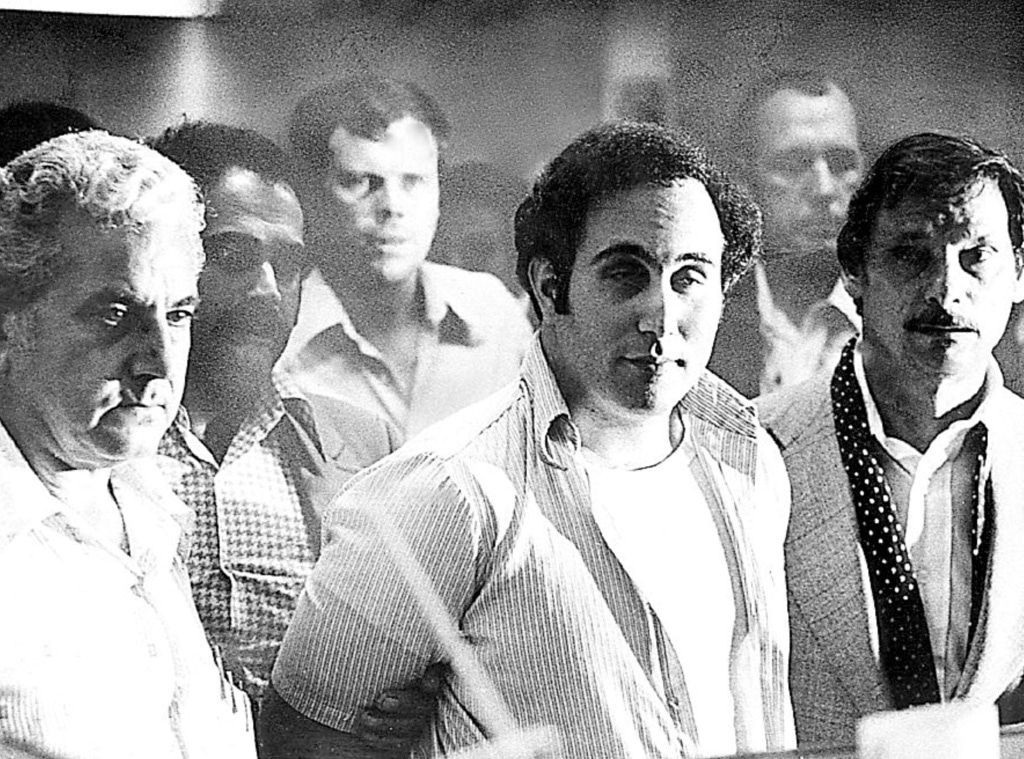

Stan Wolfson/Newsday RM via Getty Images

Stan Wolfson/Newsday RM via Getty ImagesWhy accept the already scary and strange if you can make it scarier and much, much stranger?

The going had already gotten pretty damn weird when it came to the "Son of Sam," the chosen moniker of serial killer David Berkowitz, who explained to police that he murdered six people in a spate of attacks between the summers of 1976 and 1977 on order from the dog who lived next door. Only 24 when he was caught, Berkowitz pleaded guilty to all six and was sent to prison for forever, six 25-years-to-life terms to be served consecutively.

But at least one investigator who consumed everything there was to know about the case was convinced that the real story was far more twisted.

Not unlike those who could never accept that Oswald acted alone, self-motivated journalist Maury Terry—an IBM employee when Berkowitz went on his killing spree—fully believed the delusional postal worker's later claim (from prison) that he was part of a satanic cult whose members also included brothers John and Michael Carr, the actual human sons of Sam Carr, owner of the devilish dog in question.

Terry's complicated theory, as laid out in his 1988 book The Ultimate Evil, is fully plumbed in the new Netflix series The Sons of Sam: A Descent Into Darkness, a two-pronged investigation that shows how Terry linked the Carrs (for instance, one police sketch was a dead ringer for John, who sometimes went by "Wheaties," a name invoked in one of the killer's taunting letters) and a purported cult called "the Children" to the crimes.

"It was creepy," series director Joshua Zeman said of the book in a recent interview with The Guardian. "It was suburban. New York City, sex, sin, horror-creepy. It had a Manson vibe to it going down with a New York flair."

Zeman told the New York Post that he first met Terry in 2009 when he was directing the documentary Cropsey, about the disappearance of several children on Staten Island in the 1980s, which prompted rumors of a killer who worshiped the devil and a link to "Son of Sam."

At first he was entirely skeptical of Terry's cult theory, but the more he heard—from Terry, other journalists and members of the NYPD—the more he thought there was at least something to the notion that Berkowitz wasn't the sole killer.

Before he died in 2015 at the age of 69, the case having basically taken over (and, in some ways, destroyed) his life, Terry arranged for his entire archive of work to be sent to Zeman after his death. The series is not only about the "Son of Sam," killings but also about the man who voluntarily ventured into those 13 months of terror back in the 1970s and stayed, becoming more obsessed as the years went by, a different kind of casualty.

"I want people to understand what really happened in the 'Son of Sam' case, and I wanted to give Maury Terry his due," Zeman explained to The Guardian. "But I also wanted to say to people, 'Look, be careful of going down that rabbit hole.' Maury Terry went down a rabbit hole for 40 years and never got back out."

And the whole thing already was so messed up, with plenty of terrifying details to captivate and cause sleepless nights, especially for the New Yorkers who were around for this terrifying chapter in the city's history. Particularly the young women with shoulder-length dark hair who seemed to be the killer's type.

As tends to be the case with future patterns, no one knew what they were dealing with when it all began on July 29, 1976.

Jody Valenti, 19, was dropping off her friend Donna Lauria, 18, at Donna's house in the Bronx shortly after 1 a.m. The pals were sitting in the car chatting when a man approached the vehicle and fired his gun, a .44-caliber Charter Arms Bulldog revolver, through the closed window. Valenti was wounded in the thigh and Lauria, a medical technician for a Manhattan ambulance company, was killed.

The New York Times' headline the next day grouped Lauria's death with a recent "spate of shootings" in a city already beset by an increase in crime and gun violence. "The unexplained attack was one of a number of shooting incidents that have baffled detectives in three boroughs and have left record keepers at Police Headquarters shaking their heads in disbelief," wrote the reporter, Robert McG. Thomas Jr.

One officer told the paper, "This looks like about normal for a summer weekend but not for a weekday."

The violence continued, but this perpetrator didn't strike again until Oct. 23, firing at 20-year-old Carl Denaro and Rosemary Keenan as they sat in their parked car in Queens. Denaro had a steel plate implanted in his head, per the Times, but he survived. Keenan was uninjured. The bullets in this case were also .44s.

On Nov. 27, Joanne Lomino, 18, was shot in the back while sitting on the porch of her house in Queens with her friend Donna DiMassi, 17, who was shot in the neck. Both survived, Lomino left paralyzed from the waist down.

The death count resumed Jan. 30, 1977, when Christine Freund, 26, was fatally shot while sitting in a car parked near the Long Island Railroad Station in Forest Hills, Queens. Her friend, 30-year-old John Diel, wasn't injured and drove the car into a nearby intersection, stopping traffic to get help.

"Woman killed in mystery shooting," read the Times headline. The story's opening line: "A young Wall Street worker from Queens was shot to death early yesterday, for no apparent reason, while sitting with her companion in a parked car on a quiet Forest Hills street waiting for the engine to warm up, the police said."

Seemingly few phrases are scarier when it comes to a possible motive for a killing than "for no apparent reason."

"We are checking into the possibility that cases with similar circumstances may have occurred in this borough and other boroughs over the past year or so," Queens District Attorney John J. Santucci told the paper, "and whether there are any connections between those possibly similar cases and this one."

On March 8, Virginia Voskerichian, a 19-year-old Columbia student, exited the subway in Queens and was walking toward her home in Forest Hills at about 7:30 p.m. when she was shot and killed, half a block from where Freund was murdered (which the Times noted).

Another young woman shot at close range on a "quiet street." An area resident told the Times that, after Freund's murder, a number of people in the privately owned neighborhood donated toward a fund to hire extra security but they only raised about half of the $70,000 they were told it would cost, and all the money was returned. "Now maybe everyone will take it more seriously," the woman said after Voskerichian was killed.

Santucci, the Queens D.A., told the Times it was too early to tell if the two killings were connected.

The following month, the killer calling himself "Son of Sam" started taking credit for his handiwork.

On April 17, Valentina Suriani, 18, and Alexander Esau were both killed while parked on Hutchinson River Parkway, not far from Suriani's home in the Bronx, at around 3 a.m. (Exactly one year later, Maury Terry took his future wife to the scene on their first date. "He was fascinated with the 'Son of Sam' case," Georgiana Byrne says in the series. "I listened to him. And I believed him." She also later divorced him because he was spending more energy on the case than on their marriage.)

Terry perhaps picked this particular scene, instead of one of the earlier ones, because it marked the first time the killer left a note behind. Signed "the Monster," it was rambling and largely incoherent, but it memorably said that the girls in Queens were prettier.

"He probably has suffered tremendously at the hands of a woman with these characteristics," forensic psychologist Dr. Emanuel Hammer told the Washington Post in an interview after the Suriani-Esau killings, referring to the female victims' long brown hair. "The rejection probably involved the flaunting of another man, perhaps in a parked car."

"But in any case," he added, "the rejection hit on an old wound of maternal rejection years ago, and the killings satisfy the exculpation of both traumas."

Following the killings of Suriani and Esau, the NYPD formed a task force that eventually grew to as many as 300 officers. By then dubbed the ".44-Caliber Killer" by the press, bullets that had been dug out of victims and their cars having proved the attacks were connected, the apparent perpetrator sent another letter to famed New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin, signing it "Son of Sam."

Received May 30, 1977, the letter read, in part, "What will you have for July 29? You must not forget Donna Lauria and you cannot let the people forget her either. She was a very, very sweet girl, but Sam's a thirsty lad and he won't let me stop killing until he gets his fill of blood." Police were able to lift a fingerprint from the letter. (When the Daily News published the letter a week later, more than 1.1 million copies of the issue were sold.)

A directive sent from the chief of police to all precincts in May described their suspect as "a neurotic, schizophrenic and paranoid, with religious aspects to his thinking process, as well as hintings of demonic possession and compulsion. He is probably shy and odd, a loner inept at establishing personal relationships, especially with young women."

Hammer, the forensic psychologist, had suggested in April that leaving notes could be an indicator that the killer wanted to be caught, "that this disorder is so extreme at this stage, that the man wants to bring it all to an end."

But on June 26, Judy Placido, 17, and Salvatore Lupo, 20, were shot and wounded—Placido in the head, neck and shoulder and Lupo in the arm—while sitting in a friend's car at 3:20 a.m. in Queens, having just left a nightclub less than two blocks away.

The first anniversary of Lauria's death passed. But on July 31, Robert Violante and Stacy Moskowitz, both 20 and on their first date together, saw a movie and were parked in a lovers' lane area overlooking the Brooklyn waterfront at 2:50 a.m. when each was shot in the head. Violante, shot once, lost his left eye. Moskowitz was hit twice and died later at the hospital, the only blonde female victim claimed by the "Son of Sam."

Another bullet lodged in the steering column—four shots overall, just like in the seven previous attacks.

The man who pulled the trigger—matching previous descriptions of a white male in his 20s, average build, dressed in jeans and a gray shirt—walked off into the night, crossing the street and disappearing into the park.

Despite increased patrols, the widespread media coverage and an entire city on edge (many women cut their hair short, or purposely pinned it up before going out at night), the change of borough threw investigators for a loop. Still, as soon as the report came through, the NYPD immediately put the contingency plan they called "Code 44" into effect, officers canvassing the area and stopping any lone males. Violante's father told the Times that he had warned his son to steer clear of Queens because of the prior shootings, and Robert had agreed to remain in Brooklyn on his date.

Less than two weeks later, however, on Aug. 10, 1977, Berkowitz was arrested at his home in Yonkers, the police having found him through his car. Investigators had tracked every citation left on a vehicle parked anywhere near the site of Moskowitz's murder in Brooklyn.

Berkowitz had left his cream-colored Ford Galaxy sedan next to a hydrant and got a ticket.

When officers arrived at his address, the Galaxy was parked in front. Peering through the window, they could see what looked like the butt of a machine gun sticking out of a bag. They found the .44-caliber revolver, loaded, in the car as well, and another submachine gun in his apartment.

When they put the cuffs on Berkowitz, he reportedly said, "Well, you've got me."

New York City Mayor Abe Beame said at a 1:30 a.m. news conference at 1 Police Plaza in Manhattan, "I am very pleased to announce that the people of the City of New York can rest easy tonight because police have captured a man they believe to be the 'Son of Sam.'"

A Westchester deputy sheriff told the Times that he used to live in Berkowitz's apartment building and, while he didn't figure him to be "Son of Sam," he did believe the young postal worker had been sending him threatening letters. The deputy eventually reported him to the NYPD, who then had his name when they were running the parking tickets.

"From the beginning I had just wanted 10 minutes with him in a motel room so I could find out about the guy I'd been hunting for six months," task force member Detective Gerald Shevlin told the New York Times after the surprisingly forthcoming suspect was in custody. Instead, "Room 1312" at the precinct was where the magic happened. "We went in there and wrapped up all the loose ends."

Sgt. Joseph Conlon described Berkowitz as "cooperative" and "calm." And "talkative."

Berkowitz had calmly explained to the half-dozen officers who crowded into 1312 that Sam Carr, his neighbor on Pine Street in Yonkers, was actually the devil, and had commanded Berkowitz to kill via messages relayed by Sam's dog. At the time, Berkowitz was also accused of shooting the dog.

Police said that Berkowitz was able to answer questions about that first letter, the one whose contents hadn't been made public.

Starting back in the summer of 1976, Berkowitz recalled, he'd go out driving every night, "looking for a sign" that it was the right time to kill someone. The so-called sign could be something as innocuous as finding a good parking spot. He had his .44 for about a month before he shot anybody, he said.

Details he shared with police, some of which contradicted their working theories, included: He carried his gun around in a plastic bag, but never shot through the bag. The victims were chosen at random, and he was only ever targeting the women—but not because of their hair color. He wasn't seeking revenge against women for being jilted, he insisted; rather, he only killed because Sam Carr—via his dog—commanded him to shed the blood of pretty girls. He also said that Stacy Moskowitz wasn't his original target that last night; he was actually eyeing the woman in another car, but the man driving had pulled into a less well-lit parking spot (and soon saw in his rearview mirror Moskowitz and Violante being shot).

Violante had seen Berkowitz earlier in the evening, sitting on the swings in the park for close to an hour.

Berkowitz also said that he had acquired a machine gun so that he could get into a fatal shootout with police and "take some cops with me."

Defying the lawyers who suggested he plead insanity, Berkowitz pleaded guilty to all six murders on May 8, 1978.

At his sentencing the following month, however, he made a move to jump out of the seventh-floor courtroom window, screaming that Stacy Moskowitz was a "whore" and he'd kill her and everyone else again.

A subsequent psychiatric evaluation still found him competent, and on June 12 he was sentenced to at least 150 years in prison, with the possibility of parole after 25 years.

In 1987, Berkowitz said that he had become an evangelical Christian behind bars, and that people should refer to him as "Son of Hope," rather than his old nickname. Before his first hearing in 2002, he wrote a letter to New York Gov. George Pataki demanding that he not be given parole, insisting he "deserved to be in prison."

He's come up for parole every two years since, until his hearing scheduled for May 2020 was postponed indefinitely due to the coronavirus pandemic. After residing at various facilities, he now lives at Shawangunk Correctional Facility outside of Wallkill, N.Y.

But Maury Terry clung to other colorful aspects of the claims made by Berkowitz in prison—such as when, in 1993, he said that he actually had only killed Donna Lauria, Valentina Suriani and Alexander Esau, and that members of the satanic cult he'd joined in 1975 were responsible for the other murders and some of the attacks, and in fact had helped plan every incident.

Berkowitz named Sam Carr's sons, John and Michael, who he was known to hang out with in Yonkers, as fellow cult members.

Both Carr brothers died not long after Berkowitz was put away—John, according to police, having taken his own life just as they were knocking on his door in North Dakota in 1978 and Michael the following year in a car accident.

Berkowitz mailed a book about witchcraft to North Dakota police in 1979, writing in a margin, "Arliss [sic] Perry, Hunted, Stalked and Slain. Followed to Calif. Stanford University"—a reference to Arlis Perry, a 19-year-old Stanford student from the Peace Garden State who was murdered in October 1974, her desecrated body found posed inside Stanford Memorial Church. In 2018, police announced that they had finally been closing in on a suspect, 72-year-old Stephen Blake Crawford, a night watchman at Memorial Church when Perry was killed, but Crawford fatally shot himself when officers arrived at his apartment to arrest him.

Terry wrote about the case in The Ultimate Evil.

Meanwhile, in 1981, after seeing Terry's reporting on him featured on TV, Berkowitz wrote to the journalist, saying, "The public will never ever truly believe you, no matter how well your evidence is presented."

While The Sons of Sam director Zeman mourns the outcome of Terry's obsession with Son of Sam and definitely thinks he tied more than a few too many disparate threads together to be entirely believable, he does think there's more to the Berkowitz case than has been common knowledge these past 45 years.

"I believe the Carr brothers were involved, and there were a bunch of crazy kids and people who used the devil as a brilliant excuse to engage in bad behavior," Zeman told the New York Post. "When we start talking about networks, that's when I become far more skeptical."

Terry, of course, was hardly the only one who thought the case went way, way deeper. Carl Denaro, one of Berkowitz's victims who also befriended Terry over the years, co-wrote the book "The Son of Sam" and Me, in which he lays out his own case for suspects other than the one who's been locked up since 1977.

In addition to it being close to 45 years since Berkowitz's killing spree began, Zeman suggested that the time was right for this series because of the central reason Terry was convinced that the truth was still out there, waiting to be exposed.

Namely, a lack of trust in the police, who in 1977 were incredibly eager—and under enormous pressure—to solve the Son of Sam case.

"If the police were transparent in the beginning, then I think he wouldn't have gone there," the director told The Guardian. "Transparency is what allows people not to go down rabbit holes." And yet, Zeman observed, Terry's fate is definitely also a cautionary tale for those too inclined to believe that something worse is out there, lurking just beyond the reaches of everybody else's understanding.

"It is a fine line," he said, "and that is the tragedy of Maury Terry and a lot of true crime."

The Sons of Sam: A Descent Into Darkness is streaming on Netflix.