20th Century Fox

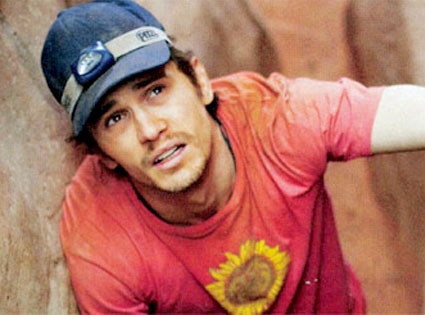

20th Century FoxReview in a Hurry: Trapped under a rock in a canyon, Aron Ralston (James Franco) must cut his own arm off to escape certain death. One half-expects a scary puppet on a tricycle to show up and say, "Hello Aron. I want to play a game," but instead, director and coscreenwriter Danny Boyle opens up his Slumdog Millionaire bag of tricks to jazz up the visuals with flashbacks, premonitions, overly dramatic soundtrack choices and hallucinations. It's all just a bit too much for this otherwise compelling true story.

The Bigger Picture: It's instructive to compare 127 Hours to the recent Ryan Reynolds thriller Buried, in that both present similar stories of cocksure pretty boys trapped in tight spaces with their lives on the line, while the respective stars deliver a bid for serious acting credibility. Buried, which never deviates from the perspective of Reynolds in a coffin for an hour and a half, is almost unbearably tense (in a good way) and demonstrates that the actor is more than just a handsome jokester.

127 Hours, on the other hand, does everything it can to show us anything other than just Franco between rocks, as if the director doesn't trust his star to be sufficiently compelling by himself. Granted, this is based on a true story, so there's only so much that can be done with the tension over how and when Aron will start slashing. And the best parts do involve just Franco, particularly a scene where he uses his mini-camera to interview himself, game-show style, about all the errors he made in getting to where he is.

But Boyle, who has always liked to play around with visuals, can't leave well enough alone. The soundtrack routinely goes from dead silence to pain-inducing, while Aron has flashes of memory, images of what could have been, Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge style imaginary escapes, visions of large crowds of people in urban settings, premonitions of his future wife...why? Mainly, it would seem, because Boyle desperately wants to hold our interest and thinks stuff has to fly by to hold an audience's attention.

Paradoxically, he achieves the opposite. By throwing so many distractions out there, he gets so far away from the central dilemma that we stop caring, and Franco's performance becomes almost a vestigial limb, severed from a thoroughly confused body.

The 180—a Second Opinion: Major props to Hanna-Barbera for allowing a creative—and utterly believable—use of Scooby-Doo. It's absurd and yet it helps to ground the story in the real world for a few moments.

Originally published Nov. 5, 2010, 9:20 a.m.